|

Illinois cop Charles Joseph Gliniewicz spent embezzled police money on porn, vacations before ‘carefully staged’ suicide |

|

| This cop shot himself in the head while driving |

A Concerning Trend In NJ: Police Officer Suicides Nearly Double In Past Decade

The recent death of a cop brought renewed attention to New Jersey police officer suicides, which have nearly doubled over the past decade.

By Tom Davis (Patch Staff) - Updated April 7, 2016 10:35 am ET

Police officers suicides in New Jersey are on the rise, and the state's finest are looking to spread awareness - and perhaps find solutions - to the growing problem.

The New Jersey State Policemen's Benevolent Association has reported that 19 officers committed suicide in 2015 - compared to 55 suicides involving N.J. law enforcement between 2003 and 2007, an average of 11 suicides a year.

Nearly a decade after the N.J. Police Suicide Task Force put together a report showing that the suicide trend was on the rise between 2003 and 2007, the union remains frustrated that the trend continues upward, noting that six have died so far this year.

"For every one officer killed in the line of duty (nationally), 6 will take their own life," said Capt. James Ryan of the South Brunswick Police Department, who has served as a spokesman for the New Jersey State Policemen's Benevolent Association.

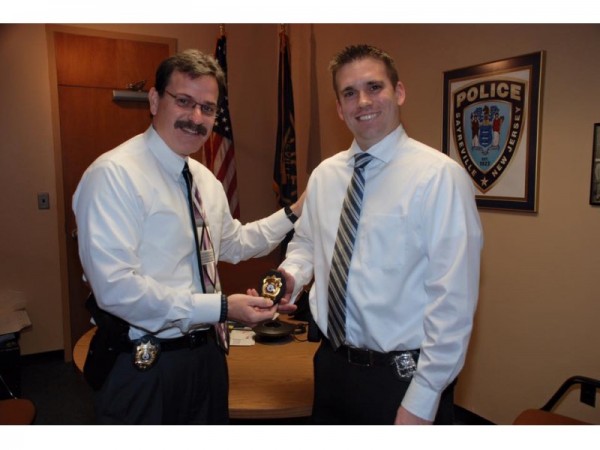

The recent death of a Sayreville cop brought renewed attention to New Jersey police officer suicides, particularly since they're 30 percent more likely to commit suicide than the general population.

Ryan acknowledged that stress is always an issue, saying the union and others are doing everything they can to address the problem.

"It's the inherent nature of our job," he said. "It's the highs and lows of our job."

Detective Matthew Kurtz, 34, who once saved an 83-year-old man in a fire, was found outside the Amboy Cinemas building off the Garden State Parkway last month, the victim of suicide, authorities said.

Sayreville Police Chief John J. Zebrowski said the officer's death "sheds more light on an insidious predator that has taken his life and so many others in law enforcement as well."

"Sadly, suicide remains a leading cause of police officer deaths," he said. "Thus, the method by which he lost his life does not make our loss any less tragic. In fact, it leaves only a greater void as many questions will remain unanswered."

He also said on the department's Facebook page, following Kurtz's death:

"I am reminded of the last paragraph in the Police Officer Prayer to Saint Michael which reads: 'We will be as proud to guard the throne of God as we have been to guard the city of men.' The men and women of the Sayreville Police Department are confident that Matthew is now on that Watch and adeptly handling those duties.

"Once again, we greatly appreciate the respectful and considerate support that has been received."

In a recent study, the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health noted that the problem is not confined to New Jersey, though national numbers of suicide have actually dropped.

A six-month sampling - July through December - of suicides was taken during 2015, showing a total of 51 police suicides nationwide.

In the journal's 2012 study of police suicides, there were 141 in 2008, rising slightly to 143 in 2009 before dropping to 126 in 2012.

"This is encouraging news that we tentatively attribute to the increased number of departments adopting peer support programs and the increased willingness of officers, many of them younger, to seek professional assistance—not only when they have a problem, but before problems develop," according to the The Badge of Life website, a police officer support site that published the study.

Indeed, the New Jersey suicide task force report identified the prevalent causes of suicides involving the state's police officers - even as it's still not clear what drove Kurtz to end his life, despite the fact that he was considered a "hero" among police officers.

The report noted that the most common risk factor for suicide is a mental illness, particularly depression or bipolar disorder, which can often act as silent and undetected problems among police officers.

Other issues, according to the report (http://www.nj.gov/oag/library/NJPoliceSuicideTaskForceReport-January-30-2009-Final(r2.3.09).pdf), that are considered lethal include the fact that police officers have easy access to firearms, which could explain why the suicide rate among cops is so much higher than that of the general public.

Others issues identified include relationship problems, particularly with intimate partners, as well as acute crises on the job.

"Stress stemming from upsetting or critical incidents present a unique occupational hazard for law enforcement officers," according to the report. "Finally, factors related to shift work and the consequences of officer schedules for family relationships are also significant."

The NJSBA noted that they're working to spread awareness of the problem through the media, in schools and also on the web, providing police officers with the tools they need to deal with stressful situations.

While the work of the task force ended with the Corzine administration, Ryan noted New Jersey has a Cop 2 Cop crisis intervention hotline that offers police confidential peer counseling. It's also staffed 24 hours daily by volunteer retired law enforcement personnel and mental health professionals.

The NJSBA provides a 24-hour emergency number for Dr. Eugene Stefanelli at (732) 609-3554.

The state also provides the New Jersey Critical Incident Stress Management Team and the New Jersey Crisis Intervention Response Network, which also provide hotlines and counseling to emergency responders.

============

In 2015, 19 law enforcement and corrections officers committed suicide in New Jersey. That's a substantial increase from years past, when the numbers were closer to 10.

This jump in police deaths comes well after the state released the Police Suicide Task Force report and increased mental health resources to law enforcement back in 2009.

Cherie Castellano is the head of Cop2Cop, a peer-to-peer, 24-hour hotline for cops in pain. While the number of suicides has risen, so too have the numbers of calls to her hotline, she said.

"We're still continuing to see them using the line and averting suicides and using the services, so it's very confusing, even to me, who's supposed to be this national expert," she said. "I'm confused."

Of the 19 who died in 2015, Castellano said, only one officer had reached out to Cop2Cop.

The organization needs to think critically about how to combat stigma — a factor that keeps those with mentally illness from seeking help, she said.

Law enforcement carries with it certain risk factors for suicide.

"Easy access to a firearm has been demonstrated in a variety of research projects as being a potential element in someone's ability to both consider and complete suicide," said Castellano. "I think it's also a thankless job that has a lot of stress, a lot of vicarious trauma, which can lead to a deterioration in your health and well–being."

==========

Posttraumatic

stress disorder (PTSD) is

often called an “injury” because it actually causes dysfunction in parts of the

brain that control memory (the hippocampus) and fear (the amygdala). This causes

them to operate at cross-purposes,

leading to a host of often disabling symptoms.

Where does

PTSD even come from? As the name implies, of course, it comes from

that thing called trauma. To understand

this, however, one must recognize some simple definitions. First, “stress”

and “trauma” are two entirely

different things—yet we tend to use them interchangeably as though they mean

the same thing. Stress alone does not

cause PTSD—stress is a routine, daily part of life. It can even help you get

that promotion you’ve been seeking, finish a marathon, or plan a vacation. It’s

“a state of mental or emotional strain

or tension resulting from adverse or very demanding circumstances,” and can

result in an abundance of stomach problems, headaches and ulcers. Over fifty

percent of doctor’s visits are from stress related conditions and ailments.

“Trauma”

is entirely different. Put simply, trauma is “the result of a

perceived threat that exceeds one's ability to cope.” It goes far beyond

mere stress alone. The person senses a life-threatening danger

physically or emotionally from an event or events. There is a sense of helplessness

that goes

with it, far exceeding that experienced from mere stress. This is where PTSD

comes from.

It’s

important to remember that there

are two types of trauma that result in PTSD, however—critical incident trauma

(such as a gunfight or violent child

death) and cumulative trauma (a

series of events, such as accumulated screams, fights, or repeated exposure to

disastrous scenes).

We’re

all familiar with the trauma that

results from a critical incident—it can be compared to a Mack truck running

over you on the highway. It’s a

“headliner,” in which everyone in the office—and even the public—knows you’ve

been involved in something traumatic.

Help is, in many cases, immediate.

Cumulative

trauma is more insidious,

however. A good comparison is a

bumblebee sting. One is irritating, two

or three are more painful, and too many stings require medical attention. Cumulative

trauma may show itself at any

stage of a career and can build over the years, sometimes manifesting it just

before—or after—retirement. It can be

just as destructive to the psyche as critical incident trauma. Help is usually

delayed or non-existent

because the onset is unseen.

How do you

know if you’re suffering from

one of these injuries? There are a few

characteristics that are common to both.

Insomnia

Nightmares

and night terrors

Uncharacteristic

anger and displays of

temper

Substance

abuse

Flashbacks

Depression

Anxiety

Scattered

thinking

Suicidal thoughts

For law enforcement,

there are two keys

to avoiding the impacts of critical and cumulative trauma: prevention and

treatment. “Prevention” means doing

something proactively for yourself. One

must first recognize that police work is one of the most toxic, caustic career

fields in the world. It is rife with

potential trauma. One must—and can—head

off the trauma before it impacts you permanently. This is why we at Badge of Life recommend a voluntary,

annual “mental health check-in” with a licensed therapist of your choice. You

do this with the same diligence as seeing your doctor once a year for a

physical exam or your dentist for a cleaning and dental check.

To do this,

you may want to choose your

department’s psychologist, if there is one, or partake of the services of your

employee assistance program. Some

officers are suspicious of these avenues, however, and if you fit that category

we recommend you go “outside” a select a therapist on your own or as

recommended by others. Here, with a

small co-pay, your confidentiality is absolute (unless you’re a danger to

yourself of others).

Having a checkup

like this is for

“healthy” officers as well as those experiencing problems—it’s an opportunity

to look at the past year, see what has worked well and examine what

hasn’t. It’s a chance to identify any

trauma that has occurred or is in the process of catching up with you. It’s

an occasion to do something good for

yourself and counter the unhealthy things you’re running into on the streets.

If you need

help—if the anxiety,

sleeplessness or other symptoms are catching up with you, don’t delay. This

is where “treatment” comes into it. Get help for yourself as soon

as

possible. Doing so can save your career.

Getting help can mean seeing that licensed

therapist and, if they so recommend, getting the services of a good

psychiatrist for medications. PTSD and

depression go hand-in-hand, and a simple anti-depressant combined with therapy

can make the difference between a long, healthy career versus a disability

retirement or discharge.

If you find

yourself in immediate

danger, such as contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. They’re staffed by compassionate professionals

who are local to you, will listen, and can direct you to appropriate

assistance.

You owe these

things to yourself. Fifteen to eighteen percent of police

officers in the United States are estimated to suffer the symptoms of

PTSD. You needn’t be one of them, but if

you are, there are some things you can do about it.

Andy

O’Hara is the founder and a board member of the Badge of Life organization. Andy has

co-authored one book and has written numerous articles for publication. He is

an advanced peer support officer, working with individuals to find appropriate

help and ways to deal with law enforcement issues. Andy is a 24-year veteran of

the California Highway Patrol, was suicidal and retired with PTSD.

Illinois cop Charles Joseph Gliniewicz spent embezzled police money on porn, vacations before ‘carefully staged’ suicide

Fox Lake Officer Charles Joseph Gliniewicz "carefully staged" his own suicide, police said.

(Facebook)Fox Lake Lt. Charles Joseph Gliniewicz used the laundered “five figures” of funds on adult websites, vacations, gym memberships and other expenses.

The cop — an Army veteran affectionately known as “G.I. Joe” — died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound while on duty Sept. 1.

“There are no winners here,” Lake County Major Crime Task Force Cmdr. George Filenko said. “Gliniewicz committed the ultimate betrayal to the citizens he served and the entire law enforcement community. The facts of his actions prove he behaved for years in a manner completely contrary to the image he portrayed.”

DEATH OF ILLINOIS POLICE OFFICER TO BE RULED SUICIDE

Gliniewicz, 52, withdrew funds from the Fox Lake Police Explorer program, which trains teens who aspire to go into law enforcement, authorities said.

They estimated the cop took about “five figures” from the program's bank account, which saw at least $250,000 flow through it.

At least two people were involved in the years of crime, police said. They did not provide further information citing the ongoing investigating. But detectives are looking into whether Gliniewicz’s wife Melodie and his son D.J. are involved with the scheme, sources told WFLD-TV Wednesday night.

The Gliniewiczes declined to comment on that report through a statement their lawyer issued.

Gliniewicz was found shot to death in September.

(Facebook)ILLINOIS COP'S DEATH HAS MORE QUESTIONS THAN ANSWERS

Gliniewicz helped manage the Explorer program — and his years mocking up crime scenes for the trainees helped him stage his own death, officials said. He took elaborate steps to try to make it look like he died in a struggle, including shooting himself twice in the torso.

Gliniewicz's death set off a large, expensive manhunt for his alleged killers.

(Stacey Wescott/AP)Just before he died, Gliniewicz radioed that he was chasing three suspicious men on foot. Backup officers later found his body 50 yards from his squad car.

The Chicago Sun-Times reported that Gliniewicz was the subject of a federal sexual harassment lawsuit.

Fox Lake Police Officer Denise Sharpe accused Gliniewicz of offering to protect her job at the department in exchange for sexual favors. A judge later dismissed the lawsuit.