Teen's death prompts warnings of electric shock drowning

Sunday, June 18, 2017 02:00PM

The sudden death of a 19-year-old from Ohio has prompted a stark warning about a devastating danger.

The teen was electrocuted after jumping off of his family's boat into the water to help his father and family dog who were struggling against an undetected electrical current running through the water.

"Once that happened, the wife that was still on the boat pulled out the shoreplug that was connected to the boat and the electric current that was in the water stopped," Sgt. Walter Hodgkiss of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources said.

It's called electric shock drowning. It happens when a current from usually a 'short' in the wiring of a dock, marina or boat spreads through the water.

Last year, Jimmy and Casey Johnson's 15-year-old daughter Carmen died after her family says she was electrocuted in a lake. They say the deadly currents came from water in a light switch box that charged the dock in their Alabama backyard.

"I was in a position where I could have saved her if it would have been anything, but electrocution in the water," Jimmy Johnson said.

Several states are now considering changes. They are calling for circuit breakers near the water, and for electrical outlets, which are required in most bathrooms, that shut down when there's a short or overload.

"There are probably a lot of drownings that happen that could be from this that people don't know," Casey Johnson said.

To keep your family safe, experts say you should inspect the electrical equipment at pools, docks, boats and marinas at least once a year. And it's a great idea to get a shock alarm or similar product that warns when there's electricity in the water.

===============

Parents warn about electric shock drowning after 15-year-old girl's tragic death

Last Updated Apr 20, 2017 1:48 PM EDT

The parents of 15-year-old Carmen Johnson, who tragically died from electric shock drowning while swimming near her family’s Alabama lake house last April, are speaking out about the rarely reported phenomenon after it took the lives of two more local women this past weekend.

The two women, 34-year-old Shelly Darling and 41-year-old Elizabeth Whipple, went missing after sunbathing on Lake Tuscaloosa Friday afternoon. Their bodies were retrieved from the lake early Saturday morning. Preliminary autopsies for the two victims show the cause of death as electrocution, the Tuscaloosa County Homicide Unit told CBS affiliate WIAT on Wednesday.

“I’ve been around water all my life and I never thought that electricity in a huge body of water like that could do what it did,” Carmen’s father, Jimmy Johnson, 49, told CBS News. “It is something that even people like me now after all these years never had any idea that this even happened.”

Carmen Johnson, 15, was tragically killed from electric shock drowning while swimming near her family’s Alabama lake house on April 16, 2016.

Jimmy Johnson

Every day, about 10 people in the U.S. die from accidental drowning, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But electric shock drownings are difficult to track. It’s known as a “silent killer.”

Even a low level of electric current in the water can be extremely hazardous or fatal to a swimmer -- especially in freshwater, where experts say the voltage will “take a shortcut” through the human body.

“There is no visible warning or way to tell if water surrounding a boat, marina or dock is energized or within seconds will become energized with fatal levels of electricity,” the non-profit Electric Shock Drowning Prevention Association reports.

In fact, Johnson says, he never would have known what happened to his daughter if he hadn’t felt the electric current himself while trying to jump in to save her.

Carmen playfully jumped off the top level of the family’s boat dock into Smith Lake with her friend Reagan Gargis on April 16, 2016. Jimmy Johnson lowered a metal ladder into the water so the girls could climb out. Minutes later, he heard Reagan scream, “Help!”

“My wife thought [Carmen] had done something to her neck, which paralyzed her,” Johnson said. “She started going underwater.”

That’s when Johnson and his son, Zach, jumped in the water after the girls and immediately felt piercing electric shocks.

“Cut the power off,” Johnson yelled to his wife as he started to go in and out of consciousness.

Johnson, Reagan and Zach survived, but Carmen didn’t make it.

“Carmen was grabbing [Reagan’s] leg and was getting the majority of the shock when I came over,” Johnson said.

Carmen Johnson swims on Smith Lake near her family’s lake house in Alabama.

Jimmy Johnson

Johnson later found a light switch at the dock that was half full of water. When he put the metal ladder into the water, the electrical current from the light switch traveled through the dock to the ladder and into the surrounding water, where the girls were swimming.

“As they were swimming toward the dock, within somewhere between the 5-to-10-foot range, is when they started feeling like they couldn’t swim,” Johnson recalled.

Johnson believes that if his family had been educated about electric shock drownings this might never have happened. Now he’s sharing Carmen’s story as a warning to others, along with tips to help prevent similar tragedies from occurring.

His safety tips include:

- Use a plastic ladder, rather than a metal one, so it won’t help transfer electricity into the water.

- If you start to feel a tingle in the water, swim away from the dock, which is where most electrical issues occur.

- Check all of the wiring around your dock, including your ground fault circuit breaker.

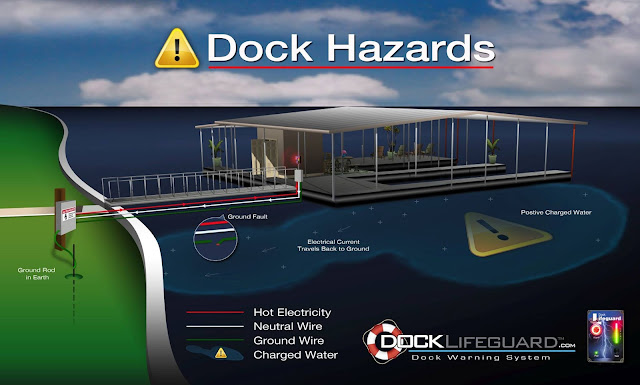

- Purchase a Dock Lifeguard, a device that detects electricity on your dock and in the water around your dock. (Johnson works with the company to promote the product.)

“It’s every homeowner’s responsibility to make sure water is safe around their dock before they start swimming,” Johnson said. “People think ‘Oh, this is a freak accident. It’s not going to happen to me.’ And here we are now — 3 dead in a year.”

==============

What every boater needs to know about Electric Shock Drowning.

One year ago, over Fourth of July weekend, Alexandra Anderson, 13, and her brother Brayden Anderson, 8, were swimming near a private dock in the Lake of the Ozarks in Missouri when they started to scream. Their parents went to their aid, but by the time the siblings were pulled from the lake, they were unresponsive. Both children were pronounced dead after being transported to a nearby hospital. About two hours later, Noah Winstead, a 10-year-old boy, died in a similar manner at Cherokee Lake, near Knoxville, Tennessee, and Noah's friend, 11-year-old Nate Parker Lynam, was pulled from the water and resuscitated but died early the following evening. According to local press reports, seven other swimmers were injured near where Noah died. These were not drowning victims. In all of these cases, 120-volt AC (alternating current) leakage from nearby boats or docks electrocuted or incapacitated swimmers in fresh water.

This little-known and often-unidentified killer is called Electric Shock Drowning, or ESD, and these deaths and injuries were entirely preventable. In just four months last summer, there were seven confirmed ESD deaths and at least that many near misses; in all likelihood, dozens more incidents went undetected. Every boater and every adult who swims in a freshwater lake needs to understand how it happens, how to stop it from happening, and what to do — and not to do — if they ever have to help an ESD victim.

Fresh Water + Alternating Current = Danger

Kevin Ritz lost his son Lucas to ESD in 1999, and he shared his story with Seaworthy in "A Preventable Dockside Tragedy" in October of 2009. Since his son's death, Ritz has become a tireless investigator, educator, and campaigner dedicated to preventing similar tragedies. "ESD happens in fresh water where minute amounts of alternating current are present," Ritz said.

What does "minute" mean exactly? Lethal amounts are measured in milliamps, or thousandths of an amp. When flowing directly through the human body, these tiny amounts of current interfere with the even smaller electrical potentials used by our nerves and muscles. Captain David Rifkin and James Shafer conducted extensive testing of all aspects of ESD for a Coast Guard study in 2008, including exposing themselves to low-level currents in fresh water. "Anything above 3 milliamps (mA) can be very painful," Rifkin said. "If you had even 6 mA going through your body, you would be in agonizing pain." Less than a third of the electricity used to light a 40-watt light bulb — 100 mA — passing directly through the heart is almost always fatal.

| Current Level | Probable Effect On Human Body |

| 1 mA | Perception level. Slight tingling sensation. Still dangerous under certain conditions. |

| 5 mA | Slight shock felt; not painful but disturbing. Average individual can let go. However, strong involuntary reactions to shocks in this range may lead to injuries. |

| 6-16 mA | Painful shock, begin to lose muscular control. Commonly referred to as the freezing current or let-go range. |

| 17-99 mA | Extreme pain, respiratory arrest, severe muscular contractions. Individual cannot let go of an electrified object. Death is possible. |

| 100-2,000 mA | Ventricular fibrillation (uneven, uncoordinated pumping of heart). Muscular contraction and nerve damage begin to occur. Death is likely. |

| 2,000+ mA | Cardiac arrest, internal organ damage, and severe burns. Death is probable. |

| Source: OSHA | |

Why fresh water and not salt? Salt-water is anywhere from 50 to 1,000 times more conductive than fresh water. The conductivity of the human body when wet lies between the two, but is much closer to saltwater than fresh. In saltwater, the human body only slows electricity down, so most of it will go around a swimmer on its way back to ground unless the swimmer grabs hold of something — like a propeller or a swim ladder — that's electrified. In fresh water, the current gets "stuck" trying to return to its source and generates voltage gradients that will take a shortcut through the human body. A voltage gradient of just 2 volts AC per foot in fresh water can deliver sufficient current to kill a swimmer who bridges it. Many areas on watersheds and rivers may be salty, brackish, or fresh depending upon rainfall or tidal movements. If you boat in these areas, treat the water as if it were fresh just to be on the safe side.

Why alternating current and not direct current (DC)? The cycling nature of alternating current disrupts the tiny electrical signals used by our nerves and muscles far more than the straight flow of electrons in direct current. "It would require about 6 to 8 volts DC per foot to be dangerous," Rifkin said, or three to four times as much voltage gradient as with AC. "Regardless of the type of voltage, the larger the voltage, the larger the gradient over the same distance." There have been no recorded ESD fatalities from 12-volt DC even in fresh water because there is less chance of the higher voltage gradient necessary developing with DC's lower voltages.

How does that electricity get into the water in the first place? In a properly functioning electrical system, all of the 120-volt AC current that goes into the boat through the shore power cord returns to its source — the transformer ashore or on the dock where it originated. For any of that current to wind up in the water, three things have to occur.

Electrical fault. Somewhere current must be escaping from the system and trying to find another path back to its source ashore.

AC safety ground fault. The AC grounding system must be compromised so that stray current cannot easily return to ground through the ground safety wire. Any stray electricity then has only one path back to its source — through the water.

No ground fault protection. Any current returning to its source through the water will create a slight but detectable difference between the amount of current traveling to the boat and returning from it through the shore power cables. Ground Fault Protection (GFP) devices, like Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters (GFCIs) required in bathrooms ashore, are designed to detect differences measured in milliamps and to shut down the electricity within a fraction of a second. If the circuit does not have one, then electricity will continue to flow into the water.

If all of these conditions exist, then some or all of the boat's underwater metals, such as the propeller, stern drive, or through-hull fittings, will be energized, and electricity will radiate out from these fittings into the water. If the boat is in saltwater, the current will dissipate without doing damage unless a diver grabs hold of the energized metal. In fresh water, 120-volt AC will set up a dangerous voltage gradient that will pass through any swimmer who bridges it.

Finding Out If Your Boat Is Leaking Current

Figuring out if your boat has a problem requires two specialized tools — a basic circuit tester and a clamp meter — that together cost about $150. If you keep your boat in a freshwater marina, the marina operator should have both and be using them to check the boats on their docks.

To determine if your boat is leaking AC, start by checking the dock wiring. Plug the circuit tester into the shore power cord receptacle you use on your pedestal. The lights on the circuit tester will tell you whether or not the shore power system is functioning as it should. There are situations where those lights can mislead you, but as a first approximation, assume all is well if the circuit tester says it is. If you find any problems, alert your marina manager or call an electrician certified to ABYC (American Boat and Yacht Council) standards.

Once you have established that the dock's electrical system is sound, take the clamp meter and put it around your shore power cord. Most electricians use a clamp meter to measure the current flowing through the neutral, hot, and ground wires separately, but we are interested in whether or not all of the current entering the boat is leaving it. If that is the case, the current passing through all of the wires will sum to zero, and that's what the meter will show when the clamp is put around the entire shore power cord. If the clamp meter shows anything but zero, either some of the current going to your boat is entering the water, or current leaking from the dock or another boat is returning to its source ashore through the metal fittings on your boat. To determine which, turn off the power at the pedestal. If the clamp meter continues to show the same reading it did when the pedestal was on, the current is coming from somewhere else. If any or all of the current goes away, then your boat is leaking some current into the water.

Unfortunately, that's not quite all there is to it. Many of the most dangerous AC loads on a boat, like air conditioning and refrigeration, are cycling loads. A fault in one of these will only show up if that equipment is running when you clamp the cord. To be sure your boat is not leaking AC into the water, you must run all your AC loads while clamping the cord and look for any reading but zero. If you find a problem, unplug your boat and don't plug it in again until you get an electrician trained to ABYC standards to figure out what is wrong and fix it.

Eliminating Current Leakage

That your boat is not leaking AC into the water right now is no guarantee that it never will. Electrical faults and ground faults develop in the marine environment all the time. There are two ways to eliminate the risk altogether.

The first — and best — alternative is to completely isolate the AC shore power system from the AC system on the boat. Then any stray AC on the boat will return to its source on the boat and will not enter the water. An isolation transformer transfers electricity from the shore to the boat and back again using the magnetic field generated by the electrical current rather than through shore wires physically touching the boat's wires. If you want to be absolutely certain your boat cannot leak alternating current into the water, install an isolation transformer.

The second alternative is to install ground fault protection in the boat's and the dock's AC system that will shut off the current if the amount of electricity going out differs by a certain amount from that returning. "The European, Australian and New Zealand standards require ground fault protection on a marina's main feeders and power pedestals," Rifkin said. "They've had zero ESD fatalities in the nearly 30 years they've had this in place." In the U.S., NFPA (National Fire Protection Association) 303 (Fire Protection Standard for Marinas and Boatyards) requires GFP devices that trip at 100 mA or lower on all docks. But these devices can be expensive to retrofit and maintain in a large marina, need to be tested monthly to keep them working properly, and are subject to nuisance trips in the marine environment, so the requirements have not been adopted or enforced uniformly at the local level.

The ABYC made ground fault protection on boats part of the E-11 electrical standard this year. Equipment Leakage Circuit Interrupters (ELCIs) that trip at 30 mA are to be installed on all new vessels built to ABYC standards, but very few older boats are equipped with them. Companies like North Shore Safety have started to offer easy to retrofit ELCIs and UL-approved cords with integrated ELCIs — these run from $200 to $400. Home building suppliers like Lowe's sell 15-amp pigtails equipped with GFCIs for around $30. Either of these could be used with a shore power cord from a house to a private dock to charge a boat's batteries.Since his son died 14 years ago, Kevin Ritz has comforted dozens of families who have lost children as he has, and he has encouraged them to join forces with him to educate others. His goal is to put himself out of business. If each and every boater takes responsibility for his or her boat, Ritz could get his wish

=============