MISHANDLING OF EXPLOSIVE AND/OR FLAMMABLE CHEMICALS AT LETTERKENNY ARMY DEPOT LED TO THE EXPLOSION AND FIRE IN THE PAINT SHOP OF BUILDING 350

Letterkenny commander: Paint stripping chemicals sparked explosion, fire that killed two

Jennifer Fitch

Aug 16, 2018 Updated 12 hrs ago

CHAMBERSBURG, Pa. —

Eric S. Byers, 29, of Huntingdon County, Pa. died in the fire

An explosion and fire at Letterkenny Army Depot on July 19 came from an accident with a chemical in the paint shop of Building 350, depot Commander Col. Stephen Ledbetter said Thursday.

The chemical was being used in normal processes, Ledbetter said, declining to name the chemical.

Two employees died from their injuries from the 7:20 a.m. industrial accident. Another man continues to be treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

"We're certainly prayerful for his full recovery," Ledbetter said.

The depot has taken initial corrective action, including additional training and signs, he said. More steps are in the works to minimize the risks associated with chemical use.

Building 350 is an industrial-style, 320,000-square-foot building used for maintenance and upgrades on military vehicles.

The building itself did not sustain structural damage in the accident, Ledbetter said.

The Occupational Health and Safety Administration investigated the incident and has up to six months to issue a report.

Eric S. Byers, 29, of Huntingdon County, Pa., and Richard Barnes, 60, of Greencastle, Pa., died. Two people were initially treated at a hospital and released for smoke inhalation.

A depot spokeswoman declined Thursday to provide a condition update for the person still hospitalized. On Monday, she said he was in critical, but stable, condition.

Richard Barnes, 60, of Greencastle, Pa., died

Many violations have been listed in the DEP's web pages. The more recent ones state that

"Containers of hazardous waste are not closed during storage". Most likely, mishandling of the toluene-based paint or metal stripping chemicals caused the explosion and fire. According to the permit for the facility, cleanup solvents are used there. There is also a flame spay booth.

The permit also lists the following tank in Bldg. 350: ONE PAINT STRIPPING TANK, R3419 - BLDG 350

====================

CHAMBERSBURG, PA - Residents living just outside the northern gate of Letterkenny Army Depot were disturbed in 1982 to find out a neighbor had been poisoning their wells.

Residents in the area around Rowe Run Road were advised not to drink their well water. The Army went after the cause of the contamination and connected the homes to a public water system in 1987.

Today, 35 years later, the Army is entering the final stage of containing the hazardous chemicals that pollute the groundwater northeast of the depot.

Environmental regulators and the Army have agreed that “it’s impractical to treat everything to zero,” according to Bryan Hoke, installation restoration program manager. The aim is to shrink the plume of groundwater contamination back toward the depot.

The main contaminant at Letterkenny has been volatile organic chemicals -- most notably trichloroethylene, a suspected carcinogen that may affect a person’s nervous system, liver, respiratory system, kidneys, blood, immune system, heart and body weight.

Letterkenny has been a vehicle maintenance shop for the Army, and from the 1950s to 1970s workers used VOCs to degrease parts. They sometimes dumped the solvents on the ground in expectation that the chemicals would evaporate, Hoke said. Instead, the VOCs seeped into the ground.

Some hazardous chemicals also seeped from a cracked concrete lagoon where industrial wastes settled and from leaking underground pipes. Metals, such as lead and chromium, were also found and removed.

The Army has spent $152 million since 1980 to clean up toxic waste at Letterkenny Army Depot, and is planning to spend another $28 million to finish the job. Hoke said that active treatment of pollution at Letterkenny is expected to end in five years, then monitoring of water wells will continue for another 25 years.

“We haven’t identified anything new since the mid-1990s,” Hoke said. “There are no easy fixes to the groundwater. We did the easy fix digging up the soils.”

The community has all but lost interest in the drawn-out, expensive cleanup, but the pollution has affected commercial development in the area, particularly on land the 1995 Base Realignment and Closure Commission ordered returned to the community.

“Environmental issues brought to the forefront that Letterkenny has a responsibility to be a good neighbor,” said L. Michael Ross, President of the Franklin County Area Development Corp. “They have become a friendly, engaging neighbor. It was started unfortunately by pollution. They’ve taken their responsibility seriously. The depot has won environmental awards. I think the environmental issues have raised the consciousness of taking safety precautions so we don’t have a repeat of what happened in the 1950s, 60s and 70s when the environmental conditions were created.”

More: Roving Letterkenny teams keep Army missiles accurate

Letterkenny, and its tenants, has been one of the county’s leading employers since its creation in 1942. With mechanical skills and limited education, residents could work near home at a well-paying career. Shop employees have taken pride in supporting troops overseas first by repairing tanks, then vehicles and most recently, missiles. The depot has always stored and disposed of munitions.

The Department of Defense spends more than a billion dollars a year to clean up the sites that its operations have contaminated with toxic waste and explosives. In military spending that’s the equivalent of 350 Patriot missiles, 1,200 mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles or a B-21 stealth bomber or two.

The military has 40,700 hazardous sites, according to a report from ProPublica. The independent non-profit newsroom based in New York City obtained internal reports from the Environmental Protection Agency.

“The Pentagon is the most prolific and profound polluter on the planet,” said Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, a national whistle-blower support organization that has chronicled insider reports of pollution and failed cleanups on military sites.

Letterkenny is not on the military’s list of the most expensive cleanups, but ranks No. 20 among installations with sites posing the greatest threat to safety, human health and the environment, according to ProPublica.

Letterkenny has more medium- to high cleanup sites (14) than any of the 170 military installations in Pennsylvania, according to ProPublica’s investigation of EPA records. Letterkenny has violated its environmental permits 27 times in the past 37 years.

Public Opinion looked at the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection records of inspections at Letterkenny during the past five years. DEP recorded nine days when the depot violated its permits. There was no mention of any spills. Repeat violations include open containers of hazardous waste and improper containment and collection systems. Violations most often were corrected.

The most recent violation was on Aug. 29, when the depot was cited for operating a solid waste facility without a permit.

DEP also cited Letterkenny five years ago for operating three paint-stripping tanks for at least 30 years without a required air quality permit from the state. The tanks give off VOCs.

Letterkenny’s history of environmental cleanup dates to the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, which was intended to pay to cleanup up sites contaminated with hazardous materials. CERCLA established Superfund sites. Two are at Letterkenny.

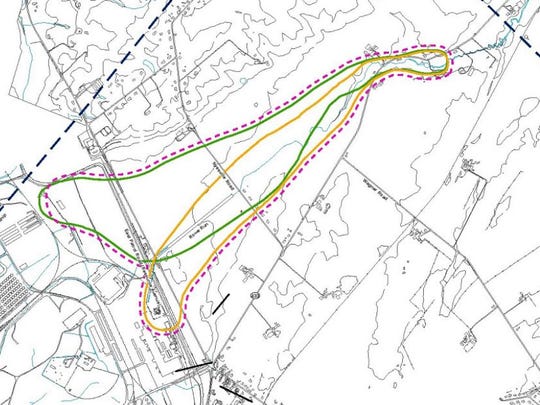

This map shows the extend of the movement of groundwater from Letterkenny Army Depot northeast along Rowe Run, between Pa. 997 and Pa. 433. (Photo: 2016 Joint Land Use Study)

By 1982, Letterkenny had been surveyed for potential contamination landfills and disposal sites. Letterkenny was the first installation in Pennsylvania to sign a cleanup agreement with the EPA. The Army in 1986 began a series of projects to remove contaminated soil on the depot.

“The remaining contamination was in the bedrock that we couldn’t get to,” Hoke said.

The chemicals in the bedrock have continued to leach into the groundwater.

The Army and regulators have agreed to two groundwater treatments – dropping potassium permanganate down some wells to speed up the oxidation of VOCs and sending electricity into the ground where electrodes heat the groundwater and evaporate the VOCs. They are to start in 2018.

The cleanup of the 122 hazardous sites on 45 acres of the depot has proceeded behind the fence and out of sight. Letterkenny’s environmental problems, however, took front and center when community leaders encouraged development in the area.

Ross said a company that made bottle caps for Tylenol was making plans in the mid-1980s to build a plant on Sunset Pike across from Letterkenny. Company officials were worried about being on well water; no one had ever figured out how seven people in the Chicago area had been murdered in 1982, but the victims all had been poisoned and had all taken Tylenol.

“We thought we had the deal done,” Ross said. “I opened my big mouth. I said Letterkenny is a Superfund site (and was installing public water lines.) That changed the decision making on the spot.”

The factory was never built.

The pollution also posed problems for redevelopment of the land that the Army is transferring to the community. BRAC 1995 ordered Letterkenny to give back about 2,000 acres. The transfer was to be completed by 2001, but there was a hitch: Environmental cleanup first had to be designed and started for a property.

“The land still hasn’t transferred due to the fact that some land is awaiting final environmental clearances,” Ross said.

The Army has given back 917 acres and reclaimed hundreds more. The eighth and final phase of land transfer is anticipated in 2019.

The Letterkenny Industrial Development Authority created the Cumberland Valley Business Park on the former Army real estate. Often tenants have agreed to lease-purchase arrangements until the Army surrendered the property. It posed problems for companies wanting to borrow to expand.

Many deeds came with a restriction that limited the depth of excavation to 6 feet.

“We’ve been able to work around it,” Ross said. “The redevelopment of Letterkenny has exceeded all expectations. Private investment has exceeded our expectations. It’s pretty much built out to what can be done.”

All buildings in the business park are occupied and about 85 percent of land has been purchased, Ross said. The rate of build-out is comparable to that of the Chambers5 Business Park, a traditional commercial development in south Chambersburg.

One of the latest additions to the Cumberland Valley Business Park involves food, a first for the park. A poultry farm is storing and shipping eggs from a warehouse. Food processors have shied away from any possible link to Letterkenny.

“Herbruck’s has broken the mold,” Ross said. “There are no environmental concerns with their site. It’s free and clear without deed restrictions.

===================================

Letterkenny pays DEP $14,000 in back fees for VOC emissions Written by Jim Hook, Public Opinion Online | Jun 23, 2015 2:00 PM

(Chambersburg) -- Letterkenny Army Depot has been using three paint-stripping tanks for at least 30 years without a required air quality permit from the state.

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection apparently never knew the tanks had emissions until 2 years ago.

DEP spokesman John Repetz said state inspectors would check permitted sources at the depot, and Letterkenny personnel were not aware that the material in the unpermitted tanks was high in volatile organics and so did not report them.

To correct matters, Letterkenny has applied to DEP "for the construction of three existing and previously unreported paint stripping tanks."

Letterkenny provided DEP with data for the tanks' emissions in prior years and paid the corresponding air emission fees, according to Janet Gardner, spokeswoman for Letterkenny Army Depot.

Repetz said on Monday that Letterkenny paid $14,835 in back fees after the tanks were reported.

Pennsylvania in 1994 established air emissions fees to pay for the air emissions monitoring program. A facility currently pays $85 per ton of pollutant.

Gardner declined to answer questions about how the unreported tanks were discovered.

DEP's Environment Facility Application Compliance Tracking System lists nine violations from a May 2013 administrative review at Letterkenny. eFACTS tracks environmental permits and compliance throughout Pennsylvania. The violation notices issued to Letterkenny included not having an air quality plan or permits and failing to pay emissions fees.

It's unclear what regulators will do. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will handle any enforcement action because Letterkenny is a federal installation, according to Repetz.

"EPA is aware of the situation regarding Letterkenny Army Depot, and we are looking into it," said Roy Seneca, a regional EPA spokesman.

Letterkenny and its tenants and contractors comprise the largest employed in Franklin County. The work includes repairing missile systems and mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles. Paint is stripped from old vehicles and equipment , which is then repainted.

VOCs vapors may have short- and long-term adverse health effects, according to the EPA. Depending on the chemicals, a specific VOC may be highly toxic or have no known health effect.

None of the VOCs from the tanks are on EPA's Hazardous Air Pollutant list, according to Lindsay.

DEP has given preliminary approval to Letterkenny's plan to deal with VOCs from the three tanks. Letterkenny does not need to add any control equipment to meet either the best available technology or reasonably available controls required in the plan, according to Repetz.

Letterkenny always follows requirements identified in the Best Available Technology and Reasonably Available Control Technology analyses and other work practices to minimize VOC emissions, according to Gardner.

Letterkenny has other operations that are monitored for VOCs and most recently revised its plan to DEP in 2013.

"We continue to track usage and report emissions on our annual Air Emissions Inventory Report," Gardner said.

The vapors from the three unreported tanks account for about 20 to 30 percent of the total VOC emissions at the Letterkenny, according to Repetz.

Building 350 contains one paint-stripping tank, originally installed in 1971 and most recently replaced in 2003, according to Lindsay. Building 370 contains two tanks, both installed in 1985. All tanks have secondary containment in case of a spill or leak.

The tanks formerly contained a product from Turco, and currently a Eurostrip product mixture, both of which are paint stripping chemicals that emit VOCs during use, Gardner said.

Together the three tanks are expected to emit in a year nearly 30 tons of VOCs, a ton of sulfur oxides and less than a ton each of nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, dust and hazardous air pollutants, according to the permit application. DEP will hold a public hearing about Letterkenny's application for an operating permit for the tanks. The hearing will be held at 9 a.m. on July 13 at the DEP Southcentral Regional Office, 909 Elmerton Avenue, Harrisburg.

Copies of the application, DEP's analysis and other documents can be seen at the DEP regional office.

People wishing to speak at the hearing should contact Mr. Gary Helsel, P.E., Acting New Source Review Chief, Southcentral Regional Office, at 814-949-7935, no later than July 6. Oral testimony which has not been pre-scheduled will not be accepted at the hearing. Commenters are asked to provide two written copies of their remarks at the hearing. Oral testimony will be limited to ten minutes per person. Organizations are requested to designate a representative to speak on their behalf.

Written comments may be submitted to the Air Quality Program, 909 Elmerton Avenue, Harrisburg, PA 17110-8200, no later than July 23. Written comments must contain the permit number (28-05002M) and the commenter's name, address and telephone number.

The EuroStrip Di phase is a commercial stripper that utilizes monoethanolamine and is formulated according to U.S. Pat. No. 6,248,107, assigned to Chemetall PLC.