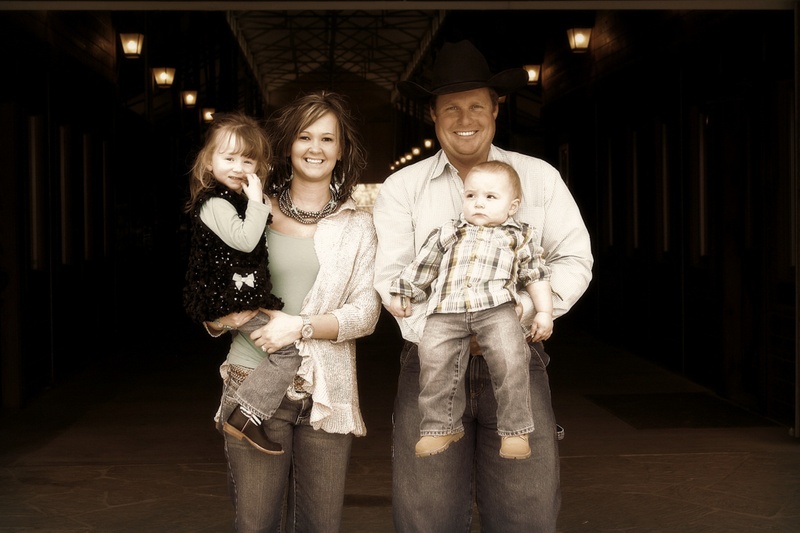

Ashley and Cody Murray, ranchers in Palo Pinto County, pose with their two children. They allege nearby gas drilling caused methane to leak into their water well before it exploded, severely burning the couple, their four-year-old daughter and Cody's father. Their legal case could put pressure on Texas regulators. Murray Family

Years after well explosion, Texas family still waiting for answers from agency

A North Texas family is still waiting for answers about whether nearby gas production caused their water well to explode and why Railroad Commission seemed to miss early signs that something like this could happen in their community.

by Jim Malewitz

March 6, 2017 12:01 AM

More than two and a half years have passed since Cody and Ashley Murray’s water well exploded, transforming their Palo Pinto County ranch into an emergency scene.

With their burns healed and gone to scars, the couple and their two young children have since returned to their 160 acres outside of Perrin, about 60 miles northwest of Fort Worth.

The Murrays still lack a trusted source of local drinking water. And they're still waiting for answers about whether nearby gas production was to blame for the fireball that shot toward Cody’s face that August day — and why the Texas Railroad Commission, the state’s oil and gas regulator, seemed to miss signs warning that something like that could happen in their cattle-and-pumpjack-sprinkled slice of the Barnett Shale.

Outside experts have linked the explosion to nearby gas drilling. The Railroad Commission won’t comment on details of its investigation, other to confirm that it remains open.

“There is nothing new to report at this time,” spokeswoman Ramona Nye told The Texas Tribune. “The Commission takes this and every incident we investigate very seriously.”

The blast was caused by a buildup of methane gas in the water well that caused enough pressure to send water spraying in the family's pump house. Ashley Murray turned off the well pump and asked her husband to investigate, and when he turned it back on, the gas exploded, severely burning Cody, his father Jim; and Alyssa, Cody’s 4-year-old daughter.

Cody Murray took the brunt of the flames; with burns on his arms, upper back, neck, forehead and nose, the former oilfield worker spent a week in a burn unit.

The Murrays sued two nearby drillers in 2015. After Houston-based EOG Resources settled, the Murrays' attorneys have turned their attention to Fairway Resources, a subsidiary of Goldman Sachs, claiming the company's well was the source of the gas that ignited.

The Murrays are seeking more than $1 million in damages in the lawsuit, now in a Tarrant County district court. Their attorneys would not make family members available for interviews.

Matthew Eagleston, president and CEO of Fairway Resources, declined to comment, citing company policy. Fairway’s attorneys did not respond to interview requests.

In a January court filing, four experts hired by the Murrays' attorneys said the wayward methane — along with chemicals from drilling mud — escaped a poorly-sealed Fairway gas well and meandered through underground fractures into the Murrays’ pump house.

The company drilled its JT Cook #2 well in 2013, and a month later the Singletons, who live a quarter mile down the road from the Murrays and have joined them in the lawsuit, told the Railroad Commission their faucets were spouting cloudy water. The explosion at the Murrays' property happened 10 months after Fairway drilled the gas well, which sits less than 900 feet from the Singletons' water well and roughly 2,000 from the Murrays' pump house.

An EnergyWire investigation published in June first highlighted gaps in the Railroad Commission’s probe, and raised questions about how closely the agency scrutinized the Singleton’s initial complaints. Railroad Commission inspectors at the time quickly ruled out energy production as a factor in the Singletons' water problems, but testing from other agencies contradicted the commission’s findings.

Christopher Hamilton, the Murrays' attorney, acknowledges the difficulty of proving that oil and gas activities — let alone a specific well — polluted a water well hundreds of feet away. But he views this case, expected to go to trial in October, as “open-and-shut.”

“It’s really incontrovertible,” Hamilton said of the evidence he’s collected. “Sometimes the science just overwhelms.”

His hired experts include: Thomas Darrah, a geochemist at Ohio State University; Franklin Schwartz, an Ohio State University hydrologist; Zacariah Hildenbrand, chief scientific officer at Inform Environmental; and Anthony Ingraffea, a civil engineering professor at a Cornell University with expertise in hydraulic fracturing.

Ingraffea wrote of at least three likely pathways for gas to escape Fairway’s well, which he said was constructed with “bare-bones” protections and operated carelessly. The well also violated commission standards, Ingraffea wrote, notably because it lacked a Bradenhead gauge, a device that could monitor pressure and help detect leaks.

Darrah, who compared gases found in local water wells to Fairway’s gas, concluded: “The JT Cook #2 oil and gas well displays a geochemical match to samples of groundwater in the Singleton's and Murray's water wells in all of the measured data.”

Hildenbrand's analysis linked a drilling mud additive found in the Murrays' water — called Chem Seal — to Fairway's drilling.

And Schwartz found fault with a Railroad Commission analysis that ruled out the Barnett Shale as a source for the Murrays' methane and suggested the gas could have naturally escaped from a shallower rock formation. The commission's experts, Schwartz said, failed to account for “physical, chemical and isotopic processes” that alter gas underground.

The Commission declined to answer specific questions about its investigation into the explosion.

“As with any incident, our technical experts base their work on the appropriate science and data necessary to complete a thorough and comprehensive investigation,” Nye said.

Rebecca Norris, who lives just west of the Murrays, doesn’t expect the commission to do much of anything.

“Oh yeah, right,” the 66-year-old retiree responded after a reporter told her that the commission was still investigating.

In September 2015, the Tribune reported that Norris, who said can see a handful of gas wells from her bedroom window, never heard back after telling the commission that her water was turning everything — the sinks, the tub — orange. Nye promised at the time to find out why her agency never followed up.

Eighteen months later, Norris said orange “crud” still settles around the bottom of drinking glasses. She said she's the only one in her house who can stomach the water, and her grown daughter and son “won’t even go near it,” when they visit. “They say it tastes terrible,” Norris said.

Norris said the Railroad Commission still hasn’t called. Nye said this week she was looking into it.

“I feel like they’re not doing their job,” Norris said. “You think: ‘Why are they not following through on what they said they’d do?’"

============

Well Explosion Could Pressure Texas Regulators

A Palo Pinto County family is suing two oil and gas operators, alleging that gas from their wells migrated into the family's water well, which exploded and burned them.

by Jim Malewitz

Sept. 2, 2015 6 AM

Ashley and Cody Murray, ranchers in Palo Pinto County, pose with their two children. They allege nearby gas drilling caused methane to leak into their water well before it exploded, severely burning the couple, their four-year-old daughter and Cody's father. Their legal case could put pressure on Texas regulators. Murray Family

While filling a cattle trough 15 months ago, Ashley Murray noticed something odd occurring in the shack housing her family’s water pump. High-pressure water was spraying everywhere. She switched off the pump, went into the house and asked her husband to take a look. So out walked Cody Murray with his father Jim.

Ashley stood holding the couple’s four-year-old daughter just outside the wood-and-stone pump house. As Jim Murray flipped on the pump, it let out a “woosh.” Cody, a former oilfield worker, knew the sound signaled danger. He threw his dad backwards — just before a fireball shot from the wellhead and transformed the Murrays’ 160-acre Palo Pinto County ranch into an emergency scene.

Somehow, everyone survived the explosion, detailed in legal filings. But the flames severely burned each of the four.

Now, as the Murrays continue their recovery, the family wants to hold someone accountable for the blast, sparked by a buildup of methane gas. They say blame lies with a pair of companies that drilled and operate two gas wells roughly 1,000 feet away from their water well.

Those gas wells are among thousands that dot the Barnett Shale, which stretches some 5,000 square miles beneath at least 25 North Texas counties.

The wells drilled and operated by Houston-based EOG Resources and Fairway Resources, a partner of Goldman Sachs, “are the only possible sources of the contamination,” the Murrays allege in a lawsuit filed last month.

(Family members were not immediately available for interviews.)

“I have scientific testing showing that Mother Nature did not put this gas in the Murrays’ well,” said Christopher Hamilton, the family’s attorney, who called it “a landmark case in Texas.”

Through a spokeswoman, EOG Resources declined to comment on the litigation, citing company policy. Fairway Resources did not respond to messages left at its Southlake office. As of Tuesday, neither company had responded in court.

Scientifically proving the case, a difficult task, would put pressure on the state's oil and gas regulator — the Texas Railroad Commission — and could reboot an emotional debate about whether years of frenzied drilling in one of the country’s largest gas fields has put groundwater at risk.

The agency has quietly investigated the Murrays' case over the past year, its records show.

The agency — which straddles the line between industry champion and watchdog — has not openly linked groundwater contamination to drilling activities, and it frequently repeats a refrain that it has not implicated hydraulic fracturing, in particular — the revolutionary method of blasting apart rock to free up gas.

“To be clear, Commission records do not indicate a single documented water contamination case associated with the process of hydraulic fracturing in Texas,” Ramona Nye, a spokeswoman, said in an email.

Lasts spring, the agency effectively shut the door on a high-profile case dating back to 2010 — once reopened — concerning methane-tainted wells in Parker County. The last agency analysis said evidence was “insufficient” to determine whether the accused driller unlocked deep-resting Barnett gas, or if the methane naturally bubbled up from shallower depths.

A few months later, five universities published peer-reviewed research concluding that oil and gas activities (but not fracking itself) tainted some of the same water wells in Parker County. High levels of methane escaped poorly constructed natural gas wells and migrated into shallow aquifers, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science paper said. Substandard cementing likely caused the problem, said the researchers, relying on a set of geochemical tracers different than what the Railroad Commission used.

The Parker County gases arrived in the aquifer without undergoing typical geologic changes, data showed, leading researchers to conclude that they came up through a pipe — likely part of a gas well — and didn’t interact with any water or rocks below the surface.

The commission panned that study and declined to reopen its investigation.

Hamilton, the lawyer for the Murrays, said his evidence points to cementing problems similar to what researchers at the five universities identified, implicating the energy companies.

That analysis, he claims, comes from a team of highly recognized scientists who are working for free, save for travel costs.

“This is the first case I’ve ever had where none of my experts will accept compensation,” said Hamilton. “These guys won’t take any money because they’re totally in it for the science and they don’t want anyone to question their credibility.”

However, the attorney said he could not immediately reveal his data, or the names of his experts because of the discovery timeline in his lawsuit.

The family's complaint details the explosion's grizzly results, including several first and second degree burns for Cody, Jim and the child. With burns on his arms, upper back, neck forehead and nose, Cody spent a week in a hospital's intensive care and burn units. With his nerves damaged, the 38-year old cannot drive — because he can't grip a steering wheel — and cannot work, the document says.

The Murrays are seeking more than $1 million in relief.

So far, the Railroad Commission has documented high methane levels in the Murray well, and others nearby. One family’s well registered methane at more than five times the federal limit. But the data were “inconclusive with respect to specific migration pathways from shallower sources,” that analysis said.

Nye said the agency is looking at records for local oil and gas wells to make sure companies built them correctly.

After examining the Railroad Commission water well analysis, Hugh Daigle, an assistant professor in the University of Texas at Austin’s department of petroleum and geosystems engineering, agreed that the data was inconclusive, and said it looked like the agency was on the right track in investigating the contamination.

“There’s a lot of different places that gas could be coming from,” he said. “They’re doing the right thing to try to figure this out.”

Meanwhile, water concerns extend beyond the Murray ranch.

Rebecca and Larry Norris, a couple living just west of the Murrays, said their water has been turning everything orange — the sinks, the tub — for the past few years, beginning around the time the drilling companies arrived.

They reported the problem to the Railroad Commission shortly after the explosion, but haven’t heard back — "not a peep," Rebecca, 65, said. (Nye said the agency was looking into why it may not have responded.) In her house sitting near six wells, Rebecca, said, “you wonder, just wonder” what's in the water.