Human Exposure and Health

Human health can be influenced by many factors, including exposure to physical, chemical, biological, and radiological contaminants in the environment. Protecting human health from environmental contaminants is integral to EPA's mission.

EPA scientists evaluate the extent to which people are exposed to contaminants in air, in water, and on land; how these exposures affect human health; and what levels of exposure are harmful. The Agency uses this information to develop guidelines for the safe production, handling, and management of hazardous substances, and to determine whether further study or public health intervention may be necessary.

EPA also tracks exposures and health condition across segments of the

population (such as gender, race, or ethnicity) or geographic location

to help identify differences across subgroups and guide public health

decisions and strategies.

This is consistent with national public health goals aimed at eliminating health disparities, and helps the Agency work toward environmental justice

by addressing a continuing concern that minority and/or economically

disadvantaged communities frequently may be exposed disproportionately

to environmental contaminants.

The ROE indicators address three fundamental questions regarding trends in human exposure and disease or conditions that may be associated with environmental factors. All three questions examined trends across the U.S. population as a whole, as well as across population subgroups and geographic regions:

Indicators: Exposure to Environmental Contaminant

- What are the trends in human exposure to environmental contaminants? Data on trends in exposure levels provide an opportunity to evaluate the extent to which environmental contaminants are present in human tissue, independent of the occurrence of specific diseases or conditions.

Indicators: Health Status

- What are the trends in health status in the United States? Trends in general health outcome indicators (including life expectancy, infant mortality, and general mortality) provide a broad picture of health in the United States. These indicators provide a general context for understanding trends in specific diseases and conditions that may in part be linked with the environment.

Indicators: Disease and Conditions

- What are the trends in human disease and conditions for which environmental contaminants may be a risk factor? This question looks at the occurrence of diseases and conditions (including cancer, asthma, and birth outcomes) that are known or suspected to be caused (to some degree) or exacerbated by exposures to environmental contaminants.

The ROE exposure and health indicators are based on data sets representative of the national population (rather than data from targeted populations) and are not tied to specific exposures or releases. They do not directly link exposure with outcome and, consequently:

- Cannot be used to demonstrate causal relationships between exposure to a contaminant and a particular health outcome.

- Cannot be directly linked to any of the indicators of emissions or ambient pollutants in Air, Water, or Land.

However, when combined with other information, such as environmental monitoring data and data from toxicological, epidemiological, or clinical studies, these indicators can be an important key to better understanding the relationship between environmental contamination and health outcomes.

Environmental Public Health Paradigm

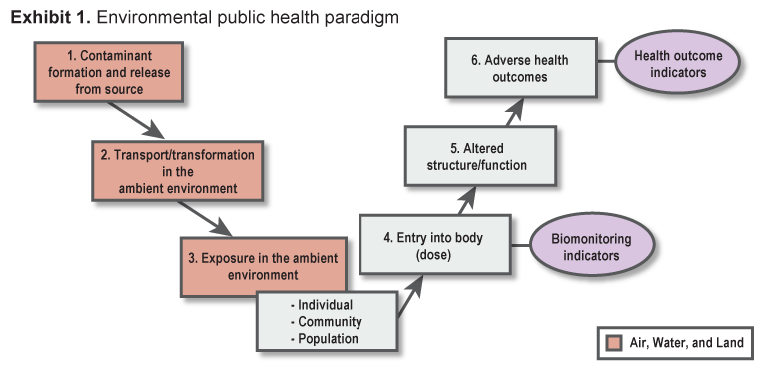

Development of disease is multi-faceted, and the relationship between environmental contamination, exposure, and disease is complex. The environmental public health paradigm shown in Exhibit 11 illustrates the broad continuum of factors or events that may be involved in the potential development of human disease following exposure to an environmental contaminant.

The presence of a contaminant in the environment or within human tissue alone does not mean disease will occur. For adverse health effects (clinical disease or death) to occur, a contaminant must:

- Be released from its source (block 1);

- Reach human receptors (via air, water, or land) (blocks 2 and 3);

- Enter the human body (via inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact) (block 4), and:

- Be present in the body at sufficient doses to cause biological changes (block 5) that may ultimately result in an adverse health effect (Block 6).

This series of events serves as the conceptual basis for understanding and evaluating environmental health. Air, Water, and Land present indicators relevant to blocks 1-3. Indicators based on data from individuals, communities, or populations (blocks 4-6) are the domain of Human Exposure and Health.

The paradigm is a linear, schematic depiction of a process that is, in reality, complex and multi-factorial. For example:

- Exposure to an environmental contaminant is rarely the sole cause of an adverse health outcome.

Environmental contaminant exposure is just one of several factors that

can contribute to the occurrence or severity of disease. Other factors

include diet, exercise, alcohol consumption, individual genetic makeup,

medications, and other pre-existing diseases. For example, asthma can be

triggered by an environmental insult, but environmental exposures are

not the “cause” of all asthma attacks. Consequently, the presence of a

disease or health outcome for which environmental contaminants are risk

factors does not mean exposure has occurred or contributed to that

disease.

- Different contaminants can be risk factors for the same disease.

For example, both outdoor air pollution and certain indoor air

pollutants, such as environmental tobacco smoke, can exacerbate asthma

symptoms.

- Susceptibility to disease is different for each person. Some individuals may experience effects from certain ambient exposure levels, while others may not.

- Much remains unknown about the extent to which environmental contaminant exposures impact health. Some environmental contaminants are considered important risk factors. In other cases, available data suggest that environmental exposures are important, but proof is lacking. And in other cases, the relationship between the contaminant and human health, if any, is not known.

Connections Between Environmental Exposure and Health Outcomes

Relationships between environmental exposures and health outcomes can only be established through well-designed epidemiological, toxicological, and clinical studies. Developing evidence that environmental contaminants cause or contribute to the incidence of adverse health effects can be challenging, particularly for effects that occur in a relatively small proportion of the population or effects with multiple causes. For example:

- In cases where exposure to an environmental contaminant results

in a relatively modest increase in the incidence of a disease or

disorder, a large sample size for the study would be needed to detect a

true relationship.

- There may be factors related to both the exposure and the health

effect—confounding factors—that can make it difficult to detect a

relationship between exposure to environmental contaminants and disease.

- In many cases, findings from studies in humans and/or laboratory animals may provide suggestive (rather than conclusive) evidence that exposures to environmental contaminants contribute to the incidence of a disease or disorder.

Nevertheless, extensive and collaborative data collection and research across the scientific community continue to strengthen understanding of the relationships between environmental exposures and disease.

EPA uses the results of scientific research to help identify linkages between exposure to environmental contaminants and diseases, conditions, or other health outcomes. These linkages, in turn, identify environmental contaminants and health outcomes of potential Agency interest. Research has established a relationship between exposure and disease for some environmental contaminants including:

- Radon and lung cancer.

- Arsenic and cancer in several organs.

- Lead and nervous system disorders.

- Disease-causing bacteria (such as E. coli) and gastrointestinal illness and death.

- Particulate matter and aggravation of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.

These known linkages guided selection of the Human Exposure and Health indicators in the ROE. However, because these indicators are based on data sets representative of the national population (rather than data from targeted populations) and are not tied to specific exposures or releases, they do not directly link environmental exposure with outcome.

References

[1] Adapted from: Sexton, K., S.G. Selevan, D.K. Wagener, and J.A. Lybarger. 1992. Estimating human exposures to environmental pollutants: Availability and utility of existing databases. Arch. Environ. Health 47(6):398-407.