Prescription for disaster: Louisiana’s opioid epidemic

Annie Ourso

June 21, 2017 | Business

Every time RoyOMartin has to replace an employee, it shells out at least $25,000 to hire and train someone new. And in recent years, the Alexandria-based lumber company has increasingly spent more to replace lost workers as a national epidemic has infiltrated the Louisiana workforce, driving up turnover and absenteeism rates, while decreasing productivity.

President and CEO Roy O. Martin III decided last fall that he had to speak out. Along with the company’s medical director, Martin penned a letter to physicians in central Louisiana, pleading with them for help.

“Over the years, we have had several employees who never returned to work after a surgery because of prescription drug dependency,” Martin wrote, asking doctors to heed the medical director’s recommendation and limit painkiller prescriptions. “I hope we can work collectively to stem the growth of the opioid epidemic.”

As the use and abuse of prescription painkillers has skyrocketed across the nation—and predominantly so in the Bayou State—Martin’s letter reflects a growing concern among businesses over the well-being of the workforce, and the costly strain of increased turnover rates and prescription drug costs, which is RoyOMartin’s fastest-growing expense.

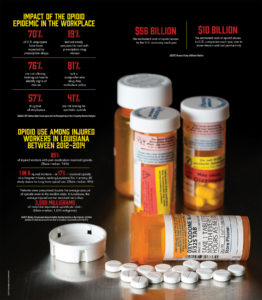

How the opioid epidemic impacts the work place. (click to enlarge)

How the opioid epidemic impacts the work place. (click to enlarge) In recent years, Louisiana has seen an alarming rise in opioid-related overdoses and become one of just eight states with more opioid prescriptions than residents. The severity of the issue prompted the state to pass legislation in June aimed at curbing the epidemic.

Less has been said, however, about an area where Louisiana’s opioid abuse also rises above the rest: its workforce. The Workers’ Compensation Research Institute reports 85% of injured workers in Louisiana on pain medication received opioids from 2012 to 2014. What’s worse, one in six received opioids on a long-term basis, making Louisiana No. 1 among 25 study states for long-term use.

The impact on workers and employers is “quite literally an epidemic,” says Jim Patterson, Louisiana Association of Business and Industry vice president of government affairs. He adds the issue has been known and talked about among the business community, but not broadly enough.

“It’s kind of a dirty little secret in the workplace,” Patterson says. “We are overdue in trying to address the problem of the overprescription of opioids.”

Employers often turn a blind eye to prescription painkiller abuse, brushing it off as a personal matter, says Dr. Luke Lee, medical director of Baton Rouge-based Prime Occupational Medicine. But, as a medical provider serving companies across south Louisiana, Lee knows the widespread nature of opioid abuse in the workforce makes it an employment issue as well as a societal one.

“The opioid crisis is just as bad as the press portrays, if not more so,” Lee says. “Based on my 20-plus years of reviewing workplace drug screens, illegal use of opioids at work increased by more than 200% over the last five years.”

Some of Louisiana’s top industries with large workforces, such as industrial contractors and petrochemical plants, involve heavy manual labor and higher risk of injury. When a worker is injured and receives prescription painkillers, it can impact their ability to show up and perform their job, especially if the worker abuses them.

“There’s the cost to the worker and then the cost to the business because they have to retrain and replace that worker when they’re out,” says Troy Prevot, executive director of LCTA Workers’ Comp. “The retraining and loss of productivity—that’s the cost to the workforce and the business right there, which passes on to the consumer.”

Dr. Luke Lee says illegal opioid use at work has increased by more than 200% over the past five years. (Photo by Don Kadair)

Dr. Luke Lee says illegal opioid use at work has increased by more than 200% over the past five years. (Photo by Don Kadair) The epidemic has also led to a spike in health care and workers’ compensation costs for employers like RoyOMartin. Safety, however, may be the most obvious and most serious concern.

Local doctors say narcotic pain medications impair users’ judgment and their ability to focus and function safely.

“Our big thing is catching it and making sure personnel are not impaired on the job,” says Shane Kirkpatrick, president of Group Contractors. “It’s hard to catch with a prescription. You don’t know if they’re taking it properly. It’s legal, but that doesn’t mean a worker is clear and should be operating a crane.”

AN EXPENSIVE EPIDEMIC

RoyOMartin has taken a proactive approach to opioid abuse by addressing the issue head-on, educating its employees and providing them with quality health care resources.

“It’s on our dashboard every day,” says Ray Peters, vice president of human resources and marketing. “We’ve had several employees, not one or two—

several—who from a workers’ comp perspective may have been injured on the job, and what happens is they go into medical treatment and opioids are used as a therapeutic drug in the process.”

But opioids were never intended to be therapeutic, he says. They’re supposed to be limited. The longer opioid use continues, the more at risk people are of addiction. Users will go from one doctor to the next, or “doctor shop,” to refill prescriptions and continue use.

“We’ve had cases where workers just continue and continue, and then fall off the face of the earth and never recover from the injury they had,” Peters says.

RoyOMartin has been able to mitigate opioid use by overseeing the medical care of injured workers. The company has a robust health care program, led by Health Services Manager Collene Van Mol and occupational nurses who can triage injuries. But when injured workers hire an attorney, seek outside care and receive prescription painkillers, their probability of returning to work declines dramatically, says Diane Davidson, employee benefits director.

Continued opioid use not only limits a worker’s ability to go back to work, it extends the length of disability in workers’ comp cases. That’s where money also comes into play, says Prevot of LCTA Workers’ Comp.

“There’s no question you can link opioid abuse to disability duration,” Prevot says. “That costs everybody.”

And in Louisiana, injured workers can technically collect temporary total disability benefits for life, says Andy Condrey, claims manager at The Gray Insurance Company, based in Metairie. The company provides insurance, claims management and loss prevention services for businesses in the oilfield and heavy construction sectors.

Insurers like Condrey and Prevot have seen first-hand the costly impact the opioid epidemic has had on businesses and workers. In most cases, Condrey says, people on painkillers are long-time users who have begun taking a combination of drugs due to the side effects of opioids, such as stomach and sleeping issues.

“We end up paying the benefits, so we see the costs go up,” Condrey says. “Drug costs are astronomical. Then you’re looking at people in their 30s who never go back to work.”

Kirkpatrick, of Group Contractors, says there is a high percentage of industrial workers with prescription painkillers for one reason or another. Kirkpatrick is a member of several professional industry organizations that he says are trying to find ways to solve the issue, such as better drug tests and shared databases with employee histories.

Contractors require drug tests, but opioids are tricky. Marijuana and cocaine, for example, are relatively simple because they’re illegal, Kirkpatrick says. If someone tests positive for painkillers and has a prescription, they pass, but employers don’t know if they’re abusing them or not. It helps to have health care providers on site or on call. Group Contractors, which has about 400 employees, has partnered with Prime Occupational Medicine and Dr. Lee, who can determine whether employees with prescriptions can operate safely based on the type of drug and exact dosage.

The opioid epidemic is also on the radar of larger industrial contractors such as Turner Industries, which has also taken steps to mitigate the impact on its business.

“Like any employer, we’re very aware of the opioid epidemic and its impact not only on Turner Industries, but the entire country,” says Dan Burke, Turner’s corporate benefits director. “In addition to closely following the stringent measures our industry has in place to ensure worker safety, Turner works closely with our pharmacy benefit manager to track opioid utilization patterns to reduce the likelihood of abuse.”

Staffing agencies that supply the industrial workforce, such as LINK Staffing Services, have also seen an increase in prescription painkiller use. LINK drug tests all applicants and has long had issues with substance abuse, says Baton Rouge branch manager Marcie Boudreaux.

“It’s more of a miracle if someone passes a drug test than if someone fails,” she says. “I’ve seen opioids more now than ever in my 14 to 15 years of doing this. If they have a prescription, we verify it with the pharmacy. But it’s kind of a catch-22 because you don’t want them operating a forklift under the influence of painkillers.”

The overflow of prescription drugs is particularly problematic in Louisiana. Perhaps no one knows this better than multi-state employers, such as Brookshire Grocery Company, which has 175 stores across Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana. The company is self insured and employs roughly 13,600 people: 8,800 in Texas, 3,800 in Louisiana and 1,000 in Arkansas.

Brookshire’s Risk Manager Eddie Crawford says that over the last five years, the company spent nearly $680,000 on prescription drug costs and almost 76% of that was spent in Louisiana—although the state had only 26% of the total workers’ comp cases and 28% of employees.

“What we see in Louisiana is worse than anywhere else,” Crawford says.

He attributes the problem to Louisiana’s poor medical treatment guidelines under the state’s Workers’ Compensation Act, as well as political influences and contributions, mostly from powerful pharmaceutical companies and the pain management sector of the medical field. That includes pain management doctors and clinics, which Crawford says did not exist until about 20 years ago.

VITAL SIGNS

The origins of the current opioid epidemic date back to the 1990s with the advent of pain management in the health care industry. But only recently has the crisis reached such proportions in Louisiana and the Capital Region that the public, and business community, has begun to take notice.

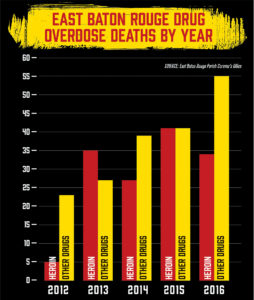

In East Baton Rouge Parish, opioid-related overdoses dramatically increased in recent years. The coroner’s office reports overdose deaths rose from 28 in 2012 to 89 in 2016—a 218% increase. Deaths by heroin overdose, meanwhile, jumped by 720% over the same span, from 5 in 2012 to a record 41 in 2015.

“It’s more of a miracle if someone passes a drug test than if someone fails,” said Marcie Boudreaux of LINK Staffing Services. (Photo by Don Kadair)

“It’s more of a miracle if someone passes a drug test than if someone fails,” said Marcie Boudreaux of LINK Staffing Services. (Photo by Don Kadair) Heroin is a highly addictive, illegal opioid that has similar—and usually much stronger—effects as prescription opioid-based painkillers. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, prescription opioid misuse can be a gateway to heroin, with nearly 80% of American heroin users reporting their abuse began with prescription pain medications. This typically happens because those who become addicted to prescription opioids eventually find it easier to find heroin, which is typically cheaper and more potent than painkillers.

Despite the stigma surrounding drug addiction, the opioid crisis seems to have touched a wide-range of the population, including people with stable lives, jobs and families. It also touches a wide range of workplaces. Seven in 10 employers say they’ve been impacted by prescription drugs, according to a 2017 National Safety Council report.

“It is the biggest concern among local employers of all types, from the university staff to the ironworkers,” says Lee.

East Baton Rouge Coroner Dr. Beau Clark says no demographic is unaffected. That’s because opioid addiction doesn’t typically originate on the streets or with random recreational use. It most often begins in a more familiar, safer setting: the doctor’s office.

“In most overdose cases we’ve worked, when we’re able to piece together the history of opioid dependence, it began with a prescription from a doctor,” Clark says. “It’s not the case that someone on a Tuesday randomly decides to shoot heroin. Usually someone has an injury, gets an opioid prescription, and it spirals from there.”

Doctors say the opioid epidemic didn’t occur on its own. There were four primary forces behind its inception: pharmaceutical companies, physicians, lawmakers and society as a whole.

The fifth vital sign—pain, and the treatment of it—became a much greater concern in the 1990s. Providers had to increasingly respond to pain, as pain treatment began playing into patient satisfaction scores. Payers like Medicaid linked scores to reimbursements. In other words, doctors became incentivized to treat pain. Clark says some of those policies are now being reversed due to the resulting epidemic.

In the 1990s, society also began to view being pain free as a right, not a privilege, adds Dr. Lee. Pharmaceutical companies capitalized on that. They also encouraged doctors to believe continuous opioid use would not lead to addiction, he says.

“Society and Congress were led to believe pain is not part of normal aspects of life, and that being pain free is a natural right,” he says. “This combination of beliefs led many doctors to prescribe opioids almost indiscriminately, which floods society with pills and ever-increasing ease of access.”

Today, it’s not uncommon to go to the hospital with an injury or for surgery and walk out with a 30-day prescription of narcotic pain pills. But medical experts and employers are now urging providers to limit prescriptions to seven days or less.

That idea has gotten through to the Louisiana Legislature, which this year approved House Bill 192, limiting first-time opioid prescriptions for acute pain to seven days. The state also passed Senate Bill 55, which expands the mandate to check the Prescription Monitoring Program database when prescribing opioids, with exceptions. It also requires providers to complete three continuing education hours on opioids as a license renewal prerequisite. Gov. John Bel Edwards has signed the bills into law.

APPROACHING TREATMENT

Although recent legislation will help to prevent further opioid abuse in Louisiana, the more difficult problem to solve will be how to help the countless people who are already using or addicted to prescription pain pills.

“What people don’t look at is what happens to people once they start taking these things,” says Gary Patureau, president of the Louisiana Association of Self-Insured Employers, which has studied the state opioid epidemic and issued a recent report calling for a workers’ comp pharmacy formulary (see related story on page 25).

Patureau points to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that found the likelihood of opioid addiction increases with each additional day of use, starting with the third day. He also references a 2016 University of Colorado study that discovered opioids actually cause increased chronic pain in lab rats, which could have implications for people.

Charting overdose deaths in East Baton Rouge Parish. (Click to enlarge)

Charting overdose deaths in East Baton Rouge Parish. (Click to enlarge) Condrey, of Gray Insurance, knows the plight of chronic opioid users from personal experience. His brother was injured working in a shipyard at 30 years old and had back surgery. Years later he hurt his back again working on air conditioning units, had surgery and was given an opioid prescription. He continued taking them for 15 years or more.

“One thing they don’t tell you is you build up a tolerance,” Condrey says. “He took more and more until he reached the maximum dose.”

Continued opioid use led to his brother’s downward spiral. He lost his marriage and was living with his mother when the addiction ultimately became too much to bear, and his brother took his own life.

Don Hidalgo, owner of Hidalgo Health Associates, which offers counseling services for the workforce, says the tendency to overprescribe painkillers, especially in workers’ comp cases, has been setting people up for addiction. He says the answer is to limit prescribing, offer alternative treatment and have doctors, psychologists and other health care providers learn how to appropriately treat addiction.

Hidalgo’s company offers Employee Assistance Programs—or EAPs—to Baton Rouge area businesses. He has partnered with more than 100 employers who provide EAPs as an employee benefit. The programs provide counseling services to employees for a range of issues, including prescription drug addiction.

While mental health services have become more common, not many services are available or covered by insurance for addiction in Louisiana, often due to the stigma surrounding substance abuse. But workplace-sponsored counseling and assistance programs often prove successful in treating addiction. Hidalgo says EAPs are a most-effective first-line of treatment and can do more to stem the opioid crisis than any laws or legislation ever could.

Since the opioid epidemic began, he says he has seen more employers reaching out for EAPs and counseling services, although they haven’t directly said that it’s due to opioid abuse in the workplace.

“There’s a hesitancy to say we have a problem in this area,” Hidalgo says. “People don’t know how to address this or have a fear of addressing it.”

Prescription pain pill addictions, and substance abuse in general, is also particularly difficult to overcome, and Hidalgo knows this better than most. In his office, Hidalgo points to a small statue of Don Quixote standing on his desk. He says he can relate to the fictional character, known for his unrealistic idealism, who embarks on a chivalrous quest to right the world’s wrongs. He compares Quixote’s quest to his own battle to rid the world of addiction.

“It’s not the easiest field to work in,” Hidalgo admits. “It’s like cancer—you don’t get a lot who recover, but you don’t give up.”