FEBRUARY 22, 2015

GARFIELD, NEW JERSEY

A pilot study using vegetable oil to remove cancer-causing

chromium that has sat under a Garfield neighborhood for three decades has

produced mixed results, leaving scientists unsure of how to clean up the

contaminated groundwater.

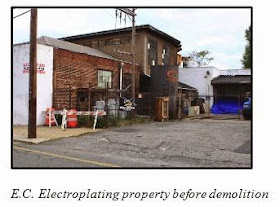

The lack of success in reducing the highest concentrations

of hexavalent chromium at the former E.C. Electroplating plant on Clark Street

is the latest hurdle for a toxic site whose initial cleanup was mishandled by

state officials, then largely forgotten for almost 30 years.

Equally uncertain is how the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency plans to pay for whatever cleanup process the agency eventually chooses.

Funding cuts have led to a waiting list for federal Superfund sites, like

Garfield, that don’t have a deep-pocketed polluter to pick up the bill.

“It’s very frustrating and it’s inexcusable,” Mayor Tana

Raymond said of the money problems. “People’s lives are at risk here. You have

to have the funds to complete the cleanup.”

The pollution dates to 1983, when more than 3 tons of

hexavalent chromium spilled into the ground from a tank at E.C. Electroplating,

a small family-run business. Although only 30 percent of the metal solution had

been recovered, the state Department of Environmental Protection allowed E.C.

Electroplating’s contractors to suspend their cleanup in 1985 — a move DEP

officials acknowledge was a mistake.

Since then, the chromium has spread underground through the

southwestern corner of the city, and dangerous levels of the contaminant have

been detected in the basements of homes and businesses. No illnesses among

residents have officially been linked to the contamination, but the federal

government considers chromium a “serious threat to human health.” Many

homeowners say their property values have plummeted.

The EPA took over the site seven years ago and declared the

neighborhood — bound by Van Winkle Avenue to the north, Monroe Street to the

south, Sherman Place to the east and the Passaic River to the west — a

Superfund site in 2011. Since then scientists have discovered that the

contaminated plume had migrated under the Passaic River into the city of

Passaic but deep enough that it’s not a risk to residents.

The EPA has already spent $5 million to clean up basements,

demolish the plant, and remove 5,700 tons of chromium-contaminated soil, 1,150

tons of concrete and 6,100 gallons of polluted water in recent years.

The agency has enough money to finish the pilot program it

began eight months ago to determine if emulsified vegetable oil pumped into the

contaminated plume will generate enough bacteria to break down hexavalent

chromium to its less toxic cousin, trivalent chromium.

The process, called anaerobic bioremediation, has reduced

the amount of hexavalent chromium on the outer edges of the former plant, said

Rich Puvogel, an EPA official who has overseen a portion of the Garfield

cleanup.

But the technique has not reduced the amount of hexavalent

chromium in the most highly concentrated spot on the plant’s property.

Scientists recently collected water samples for the last round of the pilot

test and are awaiting lab results to see if there was better progress.

“The indication is this stuff can work,” Puvogel said. “How

well it can work in the center of the site, we still need to see. But right now

there are no firm conclusions yet.”

Similar techniques have been used at 100 Superfund sites

across the nation and at other toxic sites in North Jersey, with varying

degrees of success. But the EPA sees

bioremediation as a promising method because it eliminates the transportation

and disposal of toxic material, which often end up in landfills licensed to

handle such pollution.

Another option in Garfield would be to pump the contaminated

groundwater to the surface and treat it there.

The agency will evaluate all options and make public its

preferred cleanup remedy as early as this summer, Purgovel said.

Once the EPA selects a plan, Garfield is likely to go on a

national waiting list for money to do the work.

Garfield is an “orphaned site” in EPA parlance, meaning the

government has to pay for the entire cleanup. The Calderio family, which ran

E.C. Electroplating for 75 years, have provided tax returns to the EPA to show

they cannot afford a cleanup. It’s in stark contrast to the 13 other Superfund sites

in Bergen and Passaic counties whose cleanups are being financed mostly by

deep-pocketed companies, which either polluted the sites or inherited the

liability.

Judith Enck, the EPA regional administrator for New Jersey

and New York, cited Garfield at a congressional hearing last year as a prime

example of why the government needs to restore money for Superfund cleanups.

The Obama administration recently announced an increase in

financing for long-term Superfund cleanups by $34 million for fiscal year 2016,

which begins Oct. 1 this year. But the amount won’t make up for recent cuts to

the program. Federal money for the long-term cleanup of Superfund sites dropped

to $500 million in 2014 from $605 million in 2011.

An EPA panel determines which orphan site receives money

based on risk to human health and the environment.

“It’s still pretty much status quo,” Elias Rodriguez, an EPA

spokesman, said of the financing problem. “We expect the cleanup will be in the

millions of dollars.”

Rodriguez added that once the cleanup method is chosen,

“we’ll go to the prioritization panel and wait for funding.”